Researching a novel can lead a writer down some interesting roads, writes PhD student, Laura McKenna.

When the novel is historical, there is always the lure of the twisting tracks and shadowy alleys where you can lose yourself – or chance upon some fascinating stories and background material.

My novel is set in the eighteenth century, and one of the characters is a black man who lives for a time in Ireland. The question that arises when writing such a character, is what would Ireland have been like for him. How would he have been perceived and received here in the eighteenth century?

What would his experiences of Ireland have been? What was it like for black[1] or Asian travellers and settlers two or three hundred years ago?

In the first place, it seems such travellers and immigrants were not as uncommon as one might expect. The historian, W.A. Hart, has estimated the black population in Ireland at between 2,000 and 3,000 – over the course of the latter half of the eighteenth century, rather than at any one time. As might be expected, most accounts – from newspapers, memoirs and official records – refer to individuals living near coastal towns such as Dublin, Cork, Belfast and Waterford.

Bold Sir William, a Barb, and an East Indian Black by Thomas Roberts, 1772

One of the earliest accounts of a black man in Ireland is in 1578 when Sir William Drury, in Kilkenny, ordered a blackamoor and two witches to be burnt at the stake. One hundred years later, there are sporadic mentions – a “blackamoor soldier”, one of 1500 men laying siege to Blackhall Castle in Kildare and a black servant boy at Macroom Castle brought back from Jamaica by Sir William Penn.

By the eighteenth century, there was a more significant presence, including slaves. Contemporary newspapers have occasional reports of runaways though they are mostly referred to as servants. Finn’s Leinster Journal in July 1767 cites a runaway Jonathan Rose, a black man, “who left his master’s service, Captain Kearney of Blanchville, near Gowran”, and was proficient in the French Horn and violin. Another from the Dublin Journal of 1762, advertises a runaway “black Servant Maid… We hope no Person will employ her as she is the Slave and Property of Mrs. Heyliger.” Though the advertisements regarding slaves are arresting and poignant, they are not all that different from similar ones concerning runaway native Irish indentured servants. Indeed one or two “owners” even promised to pay wages should their estranged “slave” return. Despite these advertisements, most accounts of black people in Ireland in the eighteenth century do not refer to slaves.

So who were they and how did they find themselves in this tiny outpost of Empire? Some accompanied their employers to Ireland, or were attached to a particular ship or army. A few were the result of illegitimate liaisons. For example many Protestant Irish men, middle sons, worked in the East India Company or the Bengal army and on occasion brought home a child. A smaller number came voluntarily, to preach or to work. John Jea, captured in Africa, sold into slavery in New York, eventually made his way to Ireland, where he settled and married before moving on to England. There’s a fascinating account of a company of salvage divers, working on a sunken ship in Dublin Bay, in the late 1700s using a diving bell. When the company’s owner Charles Spalding was killed (overcome by fumes in the wreck), his “Negro associate” took over. On a successful outcome, “his wife, his sister, and his moors appeared almost frantic with joy.”

There are mentions of black people throughout the eighteenth century – servants; soldiers – several accounts during the 1798 rebellion of fighters on the British and the rebel side; musicians – private, army, even an opera singer Rachel Baptiste. The first record of a black actor onstage took place in Smock Alley in Dublin in the 1770s, some fifty years before Ira Aldridge appeared in the same role of Mungo in The Padlock, in London.

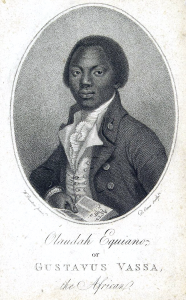

What did Irish people know of other races? The theatre provided some exposure. Many productions – often by Irish playwrights – featured black roles, played by white actors in “blackface” – usually burnt cork. These roles varied from “noble savage” caricatures in the mid-1700s to grateful or desperate slaves towards the close of the century as the opposing sides of the abolition movement became more political. The abolition debate also expanded the public’s consciousness of the plight of black slaves in the colonies. The sugar boycott was a successful propaganda coup, which spread to the major towns in Ireland. In the 1790s, one of the most influential black people of the era conducted a book tour in Ireland, promoting his biographical account of his enslavement – The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. He travelled for six months, releasing two further editions of his best seller.

Olaudah Equiano

So how were black people received in Ireland? There is some sug gestion of superstition in earlier Irish perceptions but this seems largely to do with heightened situations of battles. In two separate accounts, enemy “blackamoor” soldiers are credited with immense courage and strength – one said to be possessed of “a devil or a witch”, the other to have had “the life of a cat”.[2] These, however, are the exception. In most cases, rather than a negative response, it seems curiosity was probably more common.

gestion of superstition in earlier Irish perceptions but this seems largely to do with heightened situations of battles. In two separate accounts, enemy “blackamoor” soldiers are credited with immense courage and strength – one said to be possessed of “a devil or a witch”, the other to have had “the life of a cat”.[2] These, however, are the exception. In most cases, rather than a negative response, it seems curiosity was probably more common.

An interesting illustration of the public attitude was documented in The Freeman’s Journal in 1777. The paper sets the scene in St Stephen’s Green at noon, when a crowd of people surrounded a black woman and her child, staring and pressing so close that they frightened the woman and caused the child to cry. It took some “reasonable persons” to extricate her and help her “safe out of the walks”. The article goes on, “Had she in any manner differed from others of her colour or country so common to meet with, it might have been some apology to satisfy curiosity”. The writer goes further saying such behavior reflected scandal and ignorance on the entire assembly. The words “so common to meet with” are particularly striking.

Another marker of public attitudes is their response to mixed marriages. The few accounts that exist, suggest interest rather than racism. Freeman’s Journal in 1785 gives an account of an “extraordinary match” which took place in Drumcar, Co. Louth between a local woman and a black man. “No young girl could behave with more propriety or modesty; there was a very elegant supper prepared, and the bride and bridegroom seemed as happy as possible, and are now enjoying all the comforts of married life.” Tony Small, the escaped slave who worked for Lord Edward Fitzgerald, married the family nursemaid. John Jea, the preacher, married Mary, a “native of Ireland” (his third marriage).

These examples provide only a snapshot of life for early immigrants. But they suggest that Ireland was perhaps more racially “literate” and diverse during the eighteenth century than might be expected. Unfortunately by the end of the century, more deliberate negative ideas about race – including the “Irish race” – were being propagated, to support the vested interests of British Imperialist expansion. The Age of Enlightenment was over.

[1] From the fifteenth century onwards, the terms black, negro, moor and blackamoor were applied to a wide group of people: from those of African origin, to Muslims and Arabs, to Asians, and to indigenous people of Australia etc.

[2] Mathieu Boyd has written about the origin of the Irish phrase Fir Ghorma (blue men), meaning black men, which “corresponds to old Norse Blámenn from which the Welsh word of the same meaning, Blowmen or Blewmon, may (indirectly) derive.” In old Norse-Icelandic literature, the term blámenn is used for supernatural adversaries and “berserks” as well as “dark-skinned Muslims, and a similar development occurs in Irish.”

Further Reading

W.A. Hart. Africans in Eighteenth-Century Ireland. Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 33, No. 129 (May, 2002), pp. 19-32

Nini Rodgers. Ireland, Slavery and Anti-Slavery: 1612-1865. Palgrave Macmillan UK. 2007